This time, we’re introducing Onna no Sono no Hoshi—a stylish gag manga full of understated laughs and realistic dialogue, perfect for learners who want to enjoy slice-of-life Japanese in a fun, refreshing way.

Work Information

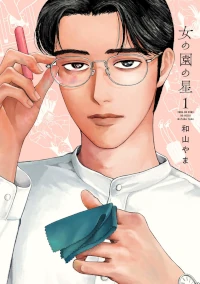

Onna no Sono no Hoshi(女の園の星)

Author: Wayama Yama

Publisher: SHODENSHA

Amount of text: plentiful

Challenge level: ★★★

Latest volume : Vol.4(Nov.2024 / Ongoing)

Story overview

This kind of humor is seriously addictive—in the best, most ridiculous way! Get ready to laugh out loud with the everyday antics of Ms. Hoshi, a teacher at an all-girls school.

Meet Ms. Hoshi, the homeroom teacher of Class 2-4. Whether she’s caught up in a game of picture shiritori in the class journal, taking care of a dog in the classroom, giving advice to a student aspiring to be a manga artist, or grabbing drinks with her colleagues after work, her days are filled with seemingly ordinary moments. But somehow, every one of them is hilariously endearing!

Why does such a simple life bring so much laughter and warmth? Discover a one-of-a-kind manga that will make you smile no matter what kind of day you’re having!

The Appeal of This Manga

Genre-wise, it’s a gag manga. The art style is realistic yet unique, with a mysterious charm that perfectly complements the quietly unfolding story.

The series follows the everyday life of Ms. Hoshi, a homeroom teacher at an all-girls school, and those around her. Each episode captures the kind of quirky, almost plausible moments that feel both familiar and fresh. Rather than making you burst out laughing, it’ll have you chuckling quietly or smiling to yourself.

With its refreshing appeal—something that hasn’t quite existed before—and its overall stylish vibe, the manga has captured the hearts of fans across Japan in recent years, regardless of gender.

Why this manga is suitable for learning Japanese

This manga is not only entertaining but also highly recommended for Japanese learners for several reasons.

Packed with Honorific Language Used in Schools

The main character, Mr. Hoshi, is a teacher who consistently uses polite language (keigo) when speaking to others. The manga showcases a wide range of keigo examples—between fellow teachers, from teachers to students, and from students to teachers—each reflecting subtle differences in nuance.

While the setting is a school, the examples of respectful speech can easily be applied to more general situations, such as conversations between coworkers in a typical office or between people of different ages. It’s a valuable resource for observing natural and contextual uses of keigo in everyday interactions.

Lots of Dialogue

This work features a relatively high volume of dialogue, making it an excellent resource for intermediate to advanced learners who want to immerse themselves in plenty of natural Japanese text.

It might be a bit challenging for beginners, but there are some chapters with lighter dialogue, so it could be a good idea to start with those and ease into it.

Phrase Spotlight

What’s in a Name? Understanding Japan’s Nickname Cultureあだな

The panel below shows a scene where Mr. Hoshi tells his students that, in the past, they used to secretly call him “MUJI” behind his back.

“Muji” refers to Muji (無印良品), a popular Japanese brand known for its minimalist, unbranded design. In this scene, the teacher’s plain clothing and neutral expression seem to remind the students of the brand—hence the nickname.

This humorous moment may seem lighthearted, but it reveals a deeper aspect of Japanese culture: the way nicknames (あだ名 or adana) are used among students and in broader society.

What Is an “Adana”?

In Japanese, the word for nickname is あだ名 (adana). While similar to English nicknames, adana carry both affectionate and critical nuances, depending on the context.

Adana often arise from:

・Physical appearance (e.g., “Megane” for someone who wears glasses)

・Personality traits (e.g., “Majime-kun” for a serious person)

・Puns or references (e.g., “Muji” based on style or behavior)

・Childhood names or speech patterns

In many cases, these names are created within tight-knit social circles such as classrooms, clubs, or sports teams.

A Familiar Pattern in Manga and Anime

Nicknames are a frequent storytelling tool in Japanese pop culture. One of the most famous is Gian from Doraemon—his nickname comes from the English word “giant,” emphasizing his large size and strong presence. Other examples include:

・Kacchan (Bakugo from My Hero Academia), showing childhood familiarity

・Chibiusa (Sailor Moon), meaning “little Usagi,” used affectionately for a younger character

・Noppo (literally “tall guy”), often used for lanky or awkward characters

Such names are more than just labels—they communicate relationships, hierarchies, and emotional closeness.

Between Affection and Alienation

In Japanese school life, adana often reflect group dynamics. A well-received nickname can create bonds, showing closeness and acceptance. For example:

・Calling a friend “Tacchan” instead of “Takeshi” might signal intimacy.

・Referring to a teacher as “Yama-chan” might soften authority into familiarity.

However, adana can also become tools for exclusion or ridicule. When based on negative traits (e.g., weight, behavior, or background), they may cross the line into ijime (bullying). This dual nature makes the practice both culturally rich and potentially problematic.

Recent Moves Toward Reform

In recent years, Japanese schools have started to reconsider the use of nicknames. Some school policies now discourage or ban adana entirely, especially when they relate to physical traits or could lead to bullying.

Teachers are encouraged to address students by their full names or surnames with honorifics (e.g., “Tanaka-san”) to promote respect and equality. These efforts reflect broader social movements in Japan to make schools safer and more inclusive environments.

Summary

Nicknames—or adana—are a distinctive feature of Japanese school life, blending affection, humor, and sometimes conflict. Whether found in classrooms or in manga, these names offer insight into group dynamics, cultural values, and language play in Japan.

For Japanese learners, understanding adana means more than just learning vocabulary. It’s a chance to explore how language reflects emotion, identity, and social structure in a uniquely Japanese way. So the next time you hear someone called “Muji-sensei,” you’ll know there’s more behind the name than meets the eye.

A Little Warning

Risk of Missing the Context

Since this is a high-concept work that presents Japanese culture from a slightly offbeat or satirical angle, international readers might find it hard to grasp exactly what makes certain parts funny or interesting.

Work Information

Onna no Sono no Hoshi(女の園の星)

Author: Wayama Yama

Publisher: SHODENSHA

Amount of text: plentiful

Challenge level: ★★★

Latest volume : Vol.4(Nov.2024 / Ongoing)

Here’s a safe and convenient way to purchase Japanese manga.

This Blog’s ConceptIn this blog, we are introducing manga that are not only highly captivating but also ideal for Japanese language learners. Studying Japanese through manga is both fun and effective. Manga allows you to understand the subtleties of keigo (honorifics), teineigo (polite speech), and casual conversation in Japanese. We hope you find works that match your interests and use them to enhance your Japanese learning journey.